There are several important drivers that are likely to affect and/or continue to affect the Australian economy in 2015. The list below is not intended as a predication or as a projection – many of the themes below are currently in place. This list is intended as a collection of the most important issues facing the economy and will provide context for the posts here during 2015.

How to characterise the current state of the economy? Its mixed coming into 2015 – some indicators are stronger than this time last year, others weaker.

Overall, the current rate of economic growth in Australia remains below the longer term average and this has been the case since 2008/09. Below is the Department of Treasury growth estimates for 2015 and beyond, as outlined in the MYEFO in December 2014.

Real GDP Growth & Projections

Source: MYEFO December 2014

The projections by the Australian Treasury for growth over the coming year is equivalent to the growth of the last two (2) years, approx. 2.5%. Using this growth figure as a starting point will help to guide the expectations of the performance of major macroeconomic components.

In a previous post, I outlined that this recent period of lower growth had coincided with an equally lengthy period of unemployment growth. Under the growth assumptions outlined above, it’s likely that unemployment and under-employment will continue to persist during 2015. At the end of 2014, just on 770k persons were counted as unemployed. That’s an increase of 55k people over 2014. For comparison, the average annual growth in unemployed persons as at December over the last 10 years was +15k. Overall economic growth will need to accelerate well above the current level and the long term average and remain there consistently before this level of unemployment is reduced. An important feature of the labour market in recent times has been the higher growth in part time over full time employed persons, as well as overall lower growth in employment. Total employment will need to grow by over 200k persons on an annual basis just to match the current level of population growth, let alone start to reduce the level of underemployment. Annual employment growth at Dec 2014 was +158k persons.

This lower growth has also coincided with lower growth in the general price level, with the exception of housing. While this lower level of price growth opens the way for the RBA to continue to stimulate via interest rate cuts, the growth in house prices (fuelled by lower rates) will likely hold the RBA back from acting. Wages growth is the lowest on record and real wages are declining, reflecting the excess capacity in the labour market. The fall in the AUD is likely to result in higher growth in tradable inflation, but will also be offset by some degree by the fall in fuel prices. The slowing growth in non-tradable inflation is more reflective of lower demand in the domestic economy – having been driven up during the Terms of Trade (ToT) boom years. Slowing income growth, reduced business investment and labour market capacity will likely weigh on the general level of prices in the economy.

Either way, I’ll be looking for deviations from this 2.5% rate of growth. The ability of the economy to grow at an accelerated rate will depend on several things:-

The commodity cycle

An enormous amount is happening on this front that will both add and subtract from growth. The transition from the investment to the production phase will have several implications:-

- Firstly, as the shift to the production phase continues, we are starting to see lower growth in mining jobs and general cost cutting to maximise profits, especially in light of falling commodity prices. Although many claim that mining doesn’t employ many people so shouldn’t have an impact on the broader economy, consider that the average full time wage in the mining industry is double the average of ALL full-time wages in Australia. As these workers shift from resources related projects the expectation is for a lower average level of earnings and hence lower consumption. Cost cutting and lower mining employment growth has already started to impact WA via lower output growth, a worsening state budget, slowing property prices & rents and negative net interstate migration.

- Secondly, while increased exports should make a positive contribution to overall growth, the most recent BREE estimates for 2014-15 suggests that this will not be the case for the total value of three out of four of our largest exports. For example, volumes for iron ore, the single largest Australian export (by value), are estimated to grow by 14%, but total value is estimated to decline by -24% (source: BREE Dec 14 Qtr. http://www.industry.gov.au/industry/Office-of-the-Chief-Economist/Publications/Documents/req/REQ-2014-12.pdf).

- Current macroeconomic forecasts by the Australian Treasury are based on a price of FOB US$60 for iron ore for the next two years (source: http://www.budget.gov.au/2014-15/content/myefo/html/01_part_1.htm). This is a far more conservative approach than in recent budgets and the current spot price is sitting around the mid-$60’s. As more supply comes online, there could be further downside to prices.

- LNG was the only major export where both volume and value were expected to grow in 2015. Latest estimates from BREE forecast export volume growth of 11% and export value growth of 7% as major projects come online for the first time. But from June 2015, the price of LNG may also come under greater pressure given that “LNG contracts tend to be based on average oil prices over the past six to nine months, recent falls [in oil prices] will not greatly impact LNG prices until the June quarter 2015” (source: BREE Dec 14 Qtr. Update).

- Thirdly, the negative impact on investment spending as major projects come online. Investment in resources projects has peaked and declining investment has been impacting growth for a while, but the expected larger falls in investment spending haven’t occurred yet.

- Role of lower Chinese demand on our export volume growth. China is our single largest export market, accounting for over 32% of Australian exports (Source: DFAT). There is much talk of a slow-down in Chinese demand linked to the popping of a credit and housing bubble. The best way to measure actual demand changes will be to watch our export growth to China. The second largest market for Australian exports is Japan, accounting for approx. 15% of our exports. The Japanese economy continues to struggle with low growth.

Can interest rates stimulate non-resources investment to “fill the gap”?

There has been some pick up in dwelling construction since the RBA lowered rates, but so far, lower interest rates have not stimulated growth in non-resources business investment. According to the latest GDP results, contribution from dwelling construction has been positive, but far smaller than the decline in private business investment. This is one of the more important indicators to watch – an increase in private business investment will be a positive signal for the economy. For the moment, lower interest rates are helping to fuel higher mortgage growth (mainly investors) rather than productive investment in the economy. Outside of dwelling construction and mining, business investment has been lacklustre in the face of subdued local and global growth. It’s unclear that any further cuts to the official cash rate would in fact stimulate business investment – business will want to see some improvement in the potential return of capex projects first.

Interest rates

- It’s more likely that rates in Australia will go lower, assuming that CPI growth continues to moderate. It will be hard for the RBA to justify rate cuts in the face of continued house price growth – but other policy measures could be put into place to keep a lid on housing lending growth at the same time (see post here). Any increase in interest rates will be great news for savers, but will be negative overall for the economy given the combination of lower income growth, unemployment and relatively high mortgage debt that is outstanding in Australia.

- US rates are the ones to keep an eye on for the moment. Any increase in rates in the US will be a step towards tighter monetary policy – this would be a big shift in policy direction, which could have a negative effect on Australian rates (i.e. higher). Despite the talk of rates going higher, current US bond rates suggest that rates will remain low, at least throughout 2015, indicating lower inflation expectations. The actions of other Central Banks also need to be taken into account – monetary policy in Europe, Japan and, to a much smaller degree, China, remain in expansionary mode to counter weaker growth in those economies. More likely rates in the US won’t increase this year, especially while other major economies are maintaining expansionary monetary policies – the impact of a rate rise in the US could see the USD continue to strengthen at a time when its own growth remains below trend.

How far will the AUD go?

This is a positive factor in favour of local import competing businesses and export focused businesses. Modelling by the RBA suggests that ideal position for the AUD is around mid the mid-0.70c mark – and we are starting the year at just below US$0.80. A lower currency will also see higher prices for imported products, so there could be some negative CPI impact. Depending on how low the AUD falls, there is a risk that interest rates in Australia may increase.

Housing

Much of our confidence, wealth and debt is tied up in the performance of house prices. Over the last year, house prices have grown by 9% across the 8 capital cities – similar to the rate of growth achieved prior to the GFC. This has been led predominantly by Sydney (+14%) while all other markets recorded growth between 7% and 2.4% (source: ABS). The best leading indicator of house prices is growth in housing finance and while there is no clear trend down, the growth in housing finance is slowing – more so for owner occupiers. Any further interest rate cuts could see another leg up in housing lending, but probably not to the same degree as previous rate cuts given higher unemployment, lower income growth and real mortgage debt almost back to its historic high levels.

The watch out for is ASIC, APRA and/or the RBA to implement policies aimed at slowing housing lending. All three (3) bodies have indicated a growing concern, especially around the growth in interest only loans.

Lower National income growth impact on consumption & housing finance

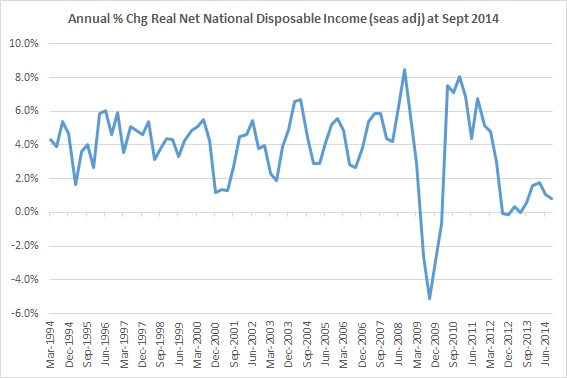

The important thing to watch for here is the combination of the continued slowdown in National income growth (and possibly even larger outright falls in National income) due to unfavourable ToT, continued excess capacity in the labour market and unemployment expectations to further impact consumption spending and growth in housing finance.

Source: ABS

The growth in National disposable income has slowed considerably since 2011 and this is likely having an impact on consumption growth.

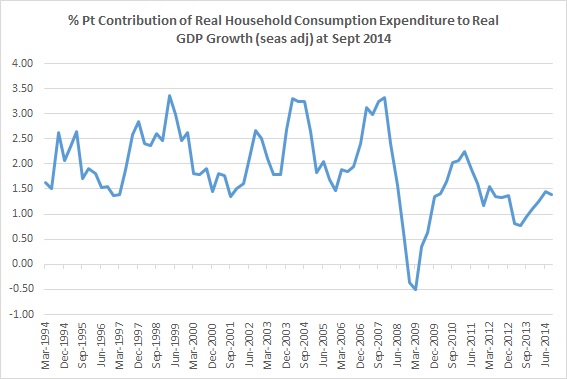

Private household consumption spending is the single largest area of expenditure in our GDP – accounting for 55% of GDP. Household consumption spending growth contributed, on average, 2.2% points to GDP growth during the commodity investment boom years (2000 – 2007). The chart below shows that this has slowed notably since the GFC and again, since 2011. In the last five years, household consumption spending has, on average, contributed 1.4% points to overall GDP growth. There is a risk that this could fall further if income growth continues to slow or declines.

Source: ABS

Government spending

So far the government has failed to generate support for its May 2014 budget. The proposed budget & reforms have not been approved through the Senate and instead of cutting the deficit, the MYEFO in December showed that the deficit has in fact become larger. According to budget analysis, most of the deterioration has been as a result of a slower economy (and overly optimistic forecasts of commodity prices). The upshot is that the budget is likely to have less of a contractionary impact on the economy. Both monetary and fiscal policy are, in effect, pointing in the same direction. Philosophically, the government is not focused on delivering an expansionary fiscal outcome, but that’s in effect what has been achieved. Unfortunately, if there is any further deterioration in the economy, it will mean an even larger deficit – something that ratings agencies will be watching. Any downgrade to our credit rating could also have a negative impact on local interest rates.

An important theme within the area of government spending is whether the government can successfully implement its infrastructure investment plan and various other structural reforms like taxation. Whilst infrastructure investment would enhance output and likely employment outside of housing and mining in the short term, it would also have long term benefits for business development and future productivity growth. The success of such a program depends heavily on whether the investment is strategic and directed to building the infrastructure that will support sustainable business development, innovation and productivity growth. Budget analysis on the future drivers of income growth highlight that productivity growth will be crucial to offset declines in the ToT and the effects of the ageing population.