The Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the December 2013 qtr was released last week. According to most media reports, the headline annual number came in “higher than expected”. The CPI is a significant data point because of how it impacts interest rate policy, which is a hot topic at the moment. So now that the Dec 2013 qtr data shows the growth in consumer prices moving into the upper half of the 2-3% band, there is all manner of speculation regarding potential interest increases.

It’s difficult to discuss CPI growth without mentioning monetary policy (interest rates) and the exchange rate. The objective of current RBA monetary policy has been to ‘rebalance’ growth in the economy – to drive growth in non-mining investment to help the economy transition from the resources investment boom. The RBA has lowered its benchmark rate to 1) stimulate greater non-mining investment and 2) break the back of a persistently high $AUD to improve the competitiveness of local manufacturers (and ability to compete with imports locally). The RBA is only just starting to get the lower dollar it has wanted and the dollar needs to presumably remain at this lower level for a while in order to generate the desired results. The problem is that lower dollar is likely to be part of the reason behind the higher annual CPI growth this qtr.

Firstly, a summary of the top line results;-

All Groups CPI (the ‘headline’ number) for December was +0.8% (Dec v Sept ’13 qtr) and +2.7% annual growth (Dec ’13 v Dec ’12). In September 2013, qtrly CPI was +1.2% and annual growth was 2.2%.

The seasonally adjusted CPI for December was +0.9% for the qtr and +2.6% annual growth. In the September qtr the seasonally adjusted CPI was +1.0% and 2.2% annual growth.

Either way you look at it, the result is the same – slightly lower qtrly CPI growth than the prior qtr, but annual growth in CPI moving higher.

The two measures of movements in the core CPI are the trimmed mean and the weighted median – both are used to measure underlying price changes by excluding volatile items. For the December qtr;

Trimmed mean (15% of the smallest & largest price movements are removed or ‘trimmed’) +0.9% for the qtr and +2.6% annual. In the September qtr the trimmed mean grew by +0.7% for the qtr and +2.3% annual.

The weighted median (price change at the 50% percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes) +0.9% for the qtr and +2.6% annual. In the September qtr, the weighted median grew by +0.6% for the qtr and +2.4% annual.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

Core inflation measures are growing in line with the headline number (qtrly & annually) – which is difficult to see in the above chart. Which means CPI growth is not driven by outlier changes.

Whilst all three measures are well within the RBA’s 2-3% target range, the upward bias is what will have some people concerned. Not that the RBA can or will do anything about the rising CPI. The idea of raising rates at this time would not be good for the Australian economy and goes against the reason why the RBA cut rates in the first place.

During the Jun, Sept and Dec 2011 qtrs the trimmed mean was growing at 2.6%, 2.7% and 2.8% respectively, well into the upper half of the range. This didn’t stop the RBA from commencing cuts to interest rates. CPI growth promptly slowed once interest rate cuts commenced, driven by offsetting low(er) growth in the tradable component.

So far though, interest rate cuts have done little to boost non-mining investment, with the exception of housing finance, which is on its highs again. Unemployment and underemployment continues to grow – which, if it continues, will start to have a greater impact on consumer spending. There are only modest indications that the lower dollar is helping manufacturing. The AIG PMI for Dec ’13 showed that contraction resumed in manufacturing. The latest NAB Business Conditions Survey for Dec highlighted another decline in manufacturing business conditions and makes a special note that many are facing higher purchasing costs as a result of the lower dollar. Capacity utilization remains low in manufacturing (73%), but hasn’t deteriorated further. This low capacity utilisation, together with weak forward orders for manufacturing (-7) suggest little likelihood of capex growth in the near term.

So what are the sources of the growth in the CPI?

The following series measures the change in the contribution, by group, to the CPI.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

There were four (4) main contributors to CPI growth in the December qtr –

Recreation & Culture (+0.24) – of which domestic travel & accommodation was the majority of the change. Note that there was not a big difference in the contribution between the Sept & Dec qtr (chart above). But the composition of the growth changed in the latest qtr. In the Sept qtr, International travel & accommodation was the bigger contributor to the CPI change. International holiday travel and accommodation continues to be a large contributor (albeit lower than in the Sept qtr) and domestic travel and accommodation has now become a bigger contributor to growth.

Housing (+0.12) – contribution of housing to CPI growth was significantly lower in the Dec qtr due to lower utilities and property rates and charges. There appears to be some seasonality related to utilities price changes (increases happen in the Sept qtr). The contribution of +0.12pts in the Dec qtr was due to changes in rents and the purchase of new dwellings by owner occupiers – both were in line with the increases of the previous qtr.

Alcohol & Tobacco (+0.12) – this was higher in Dec due to a 12.5% increase on cigarettes (from Dec 1 2013 and this price increase will be in effect each year for four years). Alcoholic beverages also saw an increase.

Food & Non-alcoholic Bevs (+0.25) – this was higher in the Dec qtr due to increases in fruit and veg prices.

There were very few categories that off-set these contributions to growth. One category that did not have as big an impact in the Dec qtr, as it did in the Sept qtr was the Transport category, namely, automotive fuels. It was one of the few categories to slightly offset price increases.

Contribution to the CPI over the full year by group;

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

Over the full year, housing, alcohol & tobacco and recreation & culture were the key contributors to CPI change.

Another way to look at the CPI is by looking at the breakdown between tradable and non-tradable categories. This provides some insight as to the extent to which price changes are attributable to domestic factors (changes in labour costs, productivity) or international factors such as exchange rate movements or changes in supply and demand in overseas markets.

Currency Movements

Before going into this detail, it’s worthwhile reviewing the movements of the AUD over this last period of interest rate cuts.

Depreciation in the AUD has been a major objective for the RBA over the last several years. RBA governor Glenn Stevens, “told the AFR in December that he would prefer the dollar closer to US$0.85c” (AFR, “80c ‘magic spot’ for $A” 25-27 Jan 2014). From the same article, “RBA board member, Heather Ridout says the dollar needs to fall to a “magic spot” between US$0.80 and US$0.85″. Under a FOI request, the RBA released documents on 28th January 2014 “discussing what the RBA regards as appropriate levels for the exchange rate considering the needs of the economy”.

At the time of writing the Aussie dollar is at US$0.8809.

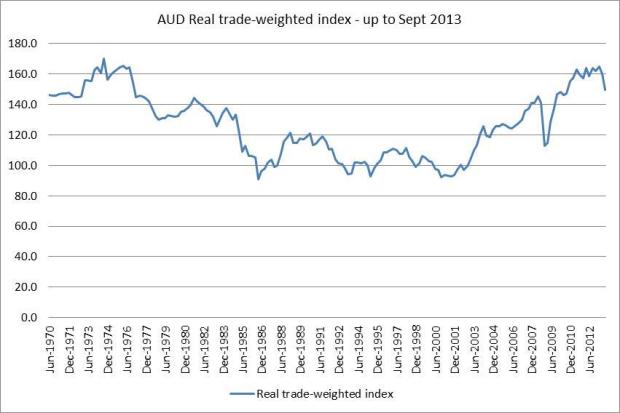

We started to see the exchange rate fall during the June qtr 2013;-

Source: RBA

Source: RBA

In the June 2013 qtr, the AUD fell by 11%, in the Sept qtr +1.3% and in the Dec qtr fell again by -4.8%. I’ve very simply taken the value of the $AUD at the start and end of the quarters to calculate the change.

On real trade weighted basis, we only started to see the big fall in the currency in the September qtr 2013 – this is the spike down in the latest observation below. This represented 6.6% depreciation.

Source: RBA

Source: RBA

From the RBA – “The ‘Real trade-weighted index’ is the average value of the Australian dollar in relation to currencies of Australia’s trading partners adjusted for relative price levels, using core consumer price indices from these countries”. This likely provides a more accurate view of the impact of dollar movements on tradable CPI.

CPI Components – Tradable and Non-tradable

Again, looking at tradable and non-tradable components is another way to gauge the source of pricing pressures in the economy – and may be even more relevant as the AUD continues to fall against the USD.

A brief explanation of the two measures is below;

- Tradable component – items whose prices are largely determined on the world market (approx. 40% of CPI by weight). Items are classified as ‘tradable’ if imports or exports represent at least 10% of supply of an item. The ‘total supply’ of an item is domestic production plus imports

- Non-tradable component – the remaining categories (60% of CPI by weight), mostly services.

This view of the CPI continues to show pockets of pricing pressure in Australia. Annual growth in the non-tradable component of the CPI is running at 3.7%, slightly lower than where it has been. This higher non-tradable component has been offset by the (relatively) lower tradable component since mid-2011. But that situation has been changing recently:-

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

Whilst the rate of growth in the non-tradable category has been fairly consistent, the rate of growth in the tradable category has been increasing since the June 2013 qtr. Given the depreciation of the AUD over the last year, it was likely that there would be some impact on price growth in the tradable category.

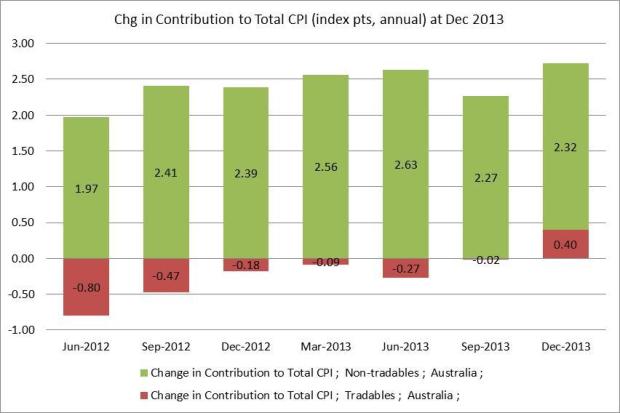

Looking at the contribution of both categories to the total CPI (annual), it does appear that there has been a shift in the source of price increases.

The contribution data is supplied by the ABS, and the addition of index points (not the index numbers) for both tradable and non-tradable categories sum to the All Groups CPI. The annual change in index points is calculated by subtracting Dec ’13 data from Dec ’12 data.

There aren’t enough qtrs of ‘contribution’ data to establish a long-term trend, but in the short term, there has been a shift in the annual change in contribution. This latest annual change has been the largest and it’s been the first time in a while where the tradable category added to CPI growth (+0.4pts) rather than offset growth in non-tradable categories.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

From an annual perspective, this may be an important shift.

Looking further into each of the categories shows the extent of the shift in the source of pricing pressure. It’s worthwhile reviewing the results of the same analysis for the CPI back in the June 2013 qtr to appreciate the extent of the shift.

Tradable Categories (items whose prices are largely determined on the world market (approx. 40% of CPI by weight), mostly imports)

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

Back in the June qtr, there were 24 tradable categories that had a negative contribution to the CPI (they offset price increases) – that has now reduced to 14 categories (and with lower values). On the flipside, the number of categories adding to CPI growth has increased from 10 to 15 categories. This change in breadth is a subtle shift that has happened behind the scenes, but is reflected in the growth of the trimmed mean and weighted median.

It’s likely that the depreciation in the AUD during this time has contributed to this shift. Categories such as international (and domestic) holiday travel were both larger contributors to CPI growth, mainly in the last two qtrs. The contribution of auto fuel jumped in the Sept qtr. Categories such as motor vehicles and audio visual continue to offset price increases, but to a lesser degree than in the past.

On the other hand, the picture for the non-tradable items looks much the same as it did in the June qtr. There are very few categories that offset growth – most non-tradable categories contributed to CPI growth – 33 out of 40 non-tradable categories.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS

The majority of the price growth still comes from the top few categories. The top six non-tradable categories contribute 53% of the increase. These are purchase of new dwellings by owner occupiers, rents, medical and hospital, domestic holiday travel and accommodation, electricity and property rates and charges. These six (6) categories also represent 41% of the weight of the non-tradable index, so would have a fairly broad impact on households.

Given that the non-tradable category is mostly service based and domestically focused, price growth in this category is sometimes thought to represent growth in labour costs. Whilst Australia does have relatively higher unit labour cost, current wage growth is at a low (wages growing, but at one of the slowest rates). The some of the main categories driving the non-tradable growth higher are not really labour intensive eg new dwelling purchases of owner occupiers, rents and electricity. Lower interest rates are more likely to be the driver of growth in the housing component in this group.

So what are the implications of this CPI report?

- RBA and interest rates – a worrying feature of the economy is the continued, albeit modest, rise in unemployment and underemployment. Lower interest rates have helped to spur housing, but not non-mining investment. With the dollar only just approaching its “magic spot”, it’s unlikely that the RBA will raise rates at this time. The challenge for the RBA will be to balance low interest rates and CPI growth. At the moment, the scales are tipped in favour of supporting demand through maintaining low interest rates.

- Real interest rates based on the official cash rate, are now negative. As CPI grows, it will eat further into the returns of savers and those on fixed income. This may act as prompt to seek out higher risk sources of income/return. For a current account deficit country, the worst case scenario is that if CPI does continue to grow, interest rates may have to rise in order to attract capital.

- The question remains over the ultimate success of interest rates to stimulate non-mining capex and investment. So far, the only lending that has been substantially impacted is housing finance (mostly swapping established dwellings for higher and higher prices), which has not grown the productive capacity of the economy, nor has it improved the labour market.

- Currency depreciation will have positive and negative impacts on the economy. Whilst it will help exporters and those locally competing with cheaper imports, it will likely increase the cost of inputs into production – the PPI will highlight the extent of this change. We are starting to see the impact of higher prices in tradable categories in the CPI, but at the same time, our manufacturing industry continues to contract. A comparison of unit labour costs among our leading trade partners (excl China) highlights the relatively higher labour costs in Australia (we are one of the highest). A lower dollar is aimed at offsetting that relatively higher cost. Ultimately the RBA may be required to perform some magic in order to keep the AUD in its ideal US$0.80 to $0.85 range. As central banks in emerging markets are finding out, this is not something in their control.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS Source: ABS

Source: ABS