At first glance, the data relating to the 4th quarter GDP was fairly straightforward. The Australian economy grew by +0.6% in the final quarter of 2015, better than the +0.4% growth expected, but well down on the previous quarter. The upward revision to the previous September quarter growth from +0.94% to +1.09% growth resulted in annual GDP growth upgraded to +2.96%. This bumped up annual GDP growth to just above average trend growth for the last 10 years. This got quite a few people excited and soon many had jumped back onto the bandwagon that the economy is transitioning well out of the mining boom. It’s always worth looking deeper into the drivers of growth and this quarter is no exception. Whilst this isn’t a bad result at all, there is still enough in the data to challenge the narrative that Australia is transitioning well.

December 2015 quarterly real GDP growth +0.63%

Despite being well down on the previous quarter, GDP growth for the December quarter was very much in line with the average for the last 10 years. This is clearly not a bad result looking at the quarterly results over the last 20 years.

Source: ABS

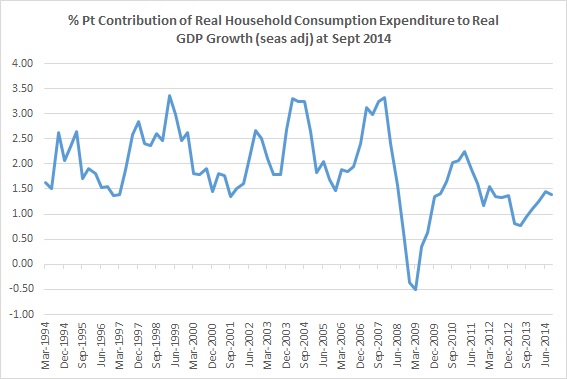

Of all the components that make up GDP, household consumption spending made the largest contribution to GDP growth on both an annual and quarterly basis.

Source: ABS

Household spending contributed over half of the growth for the year and two thirds of the growth for the quarter. It didn’t take long before this was labelled the ‘strength in the household sector’. I’ll come back to this point later.

Government consumption expenditure and net exports both made a strong positive contribution for the year, but barely contributed to growth in the latest quarter.

Private investment continued to go backwards for the year and the quarter, but government investment spending made a surprise and welcome positive contribution to growth in the latest quarter.

Inventories made a positive contribution in both the quarter and the year. Inventories represent work in progress, materials and finished goods etc. that are owned by the business, whether they are held at the business premises or elsewhere and are recorded at book value at the end of the quarter. It’s difficult to pinpoint what this means – either inventories were ramped up on higher demand expectations or lower than expected sales resulted in increased inventories. The higher contribution is the result of the ‘change in inventories’ going from negative in the previous quarter to positive in the latest quarter.

But real National Income keeps falling

Real GDP growth is a measure of the growth in the underlying output of the economy. But National Income is a better measure of the income derived from/generated by that output. The ABS recommends Real Net National Disposable Income (RNNDI) as the best measure of changes in our “economic wellbeing”. This measure “adjusts the volume measure of GDP for the terms of trade effect, real net incomes from overseas and consumption of fixed capital” (source: ABS). Using this measure, National Income continued its recent decline, falling another -1.1% for the year and -0.1% for the quarter. A big driver of this decline was the latest 12% fall in our terms of trade (ToT).

The real NNDI measure isn’t broken down into its component parts so that we can understand where/what part of National Income is driving this decline. There are several elements that make up the National Income figure – employee compensation, the gross operating surplus (corporate profit proxy) and gross mixed income (surplus/deficit from the operations of smaller unincorporated enterprises). In order to go to this more detailed level, I need to revert to Gross National Income (GNI) in current prices (nominal). In real terms national income is falling. But in nominal terms, gross national income is growing at +2.6%.

I’ve used the chart below before because it provides perspective on how much our National Income growth has slowed over the last five (5) years.

Each bar represents the annual growth in Gross National Income and shows how each component has contributed to growth in that year. Whilst National Income growth, and the contribution from its component parts, is not on its lows, it hasn’t accelerated higher in the latest year either (and we know that in real terms, National Income is declining).

Source: ABS 5206.11

The annual rate of growth in GNI has remained fairly stable over the last two quarters. But a different picture emerges when you look at the quarter on quarter growth rates.

The latest quarter National Income growth is slowing

The December quarter growth was in fact slower than in the previous quarter. The chart below looks at the same National Income components, but using the quarter on quarter growth for the last eight (8) quarters:-

Source: ABS

There are two important points I want to make about the December quarter results.

Firstly, there was a larger contribution from ‘Gross Operating Surplus’ (GOS) in the December quarter (orange bars in the chart above).

This needs to be broken down further because it doesn’t tell us much in aggregate. The GOS is the sum of private, public and financial corporation surplus (a profit proxy), general government surplus and the surplus generated by dwellings owned by persons. Here is how each of those components has contributed to growth over the last eight (8) quarters:

Source: ABS 5206.07 – the sum of these components represent the “GOS” component of National Income.

The contribution from General Government and Dwellings is fairly consistent. Business profitability, on the other hand, tells us something important about the trading environment.

According to the National Accounts, in the chart above, private non-financial corporations have made the largest contribution to growth only in the last two quarters (light blue bars), which is a large turnaround in performance compared to the prior six (6) quarters. This is the single largest component of the GOS and is probably the most important to look at in relation to underlying business conditions. We know that Mining has a large influence on the outcome of this measure. The ‘Mining’ industry accounts for a substantial 26% of corporate profits (Source: 5675.11) – no other industry group comes close to this.

According to the data in 5675.11 Business Indicators, the performance of Mining in the Sept quarter (versus the June quarter) was actually positive and which made a large contribution to the positive shift in corporate profits. But according to the same data source, Mining profits fell again in the December quarter. That would then mean that Non-Mining business profits would have had to have accelerated in the December quarter in order for total private non-financial corporations to continue to make a positive contribution overall (again I’m referring to the December quarter light blue bar in the chart above). This would be an important insight about the performance and transitioning of the economy. So did non-mining profits accelerate?

We can only get down to industry-level data by looking at Company Gross Operating Profits released by the ABS as a part of Business Indicators (5676.11) data release. You can also use 5676.15 – the direction of the data is the same between the two data sources. According to the ABS:

“Company gross operating profits data are used to compile estimates of gross operating surplus of private non-financial corporations” (Source: ABS Business Indicators)

The two measures of company profit aren’t identical, but are very similar. Comparing the results of the two measure over time, there are consistently differences in the rate of growth between the two measures, but rarely do they point in opposite directions/conflict. Except for this quarter.

Breaking down the result by industry in 5676.11 yields a very different result to that of the National Income figures.

At a total industry level, Company Gross Operating Profits declined by -2.8% in the December quarter versus the National Income figures which shows that the Gross Operating Surplus of Private non-financial corporations grew by +0.9%.

According to the data in 5676.11, the decline in Company Gross Operating Profits was driven by both Mining and Non-Mining industries in the latest quarter:-

Source: ABS 5676.11

The only quarter where Mining profits were positive was in the Sept 15 quarter, which is consistent with the stronger results in the Sept quarter.

Non-Mining is the big news here – corporate profit growth has deteriorated in the last two quarters, so much so that Non-Mining Company Gross Operating Profits declined in the December quarter. So if both Mining & Non-Mining profits declined in the latest quarter according to the Business Indicators data (5676.11), then how can the similar measure of “Private Non-Financial Corporations GOS” from 5206.07) make a larger positive contribution to National Income growth in the latest quarter?

From the ABS website (Business Indicators 5676 page):-

COMPARISON BETWEEN COMPANY GROSS OPERATING PROFITS AND GROSS OPERATING SURPLUS

Valuation changes have had an impact on the value of inventories held by Australian businesses this quarter. An inventories valuation adjustment (IVA) is applied in the calculation of the gross operating surplus of private non-financial corporations (GOS) estimate in the Australian National Accounts. The IVA for the December quarter 2015 is -$1,369m which is $1,974m lower than the September quarter 2015 IVA of $605m.

No adjustment is made to the company gross operating profits (CGOP) estimate in this publication and, as a result, users should exercise caution when comparing CGOP and GOS (my emphasis). It should be noted that there are other differences between the two series. In particular, changes are made to GOS when annual benchmarks are applied and slightly different seasonal factors apply to the two series. Given this, while CGOP movements are an appropriate indicator for GOS, the two series will not have equivalent seasonally adjusted movements from quarter to quarter. (Source: ABS – Business Indicators Dec 2015)

So comparison between the two measures is problematic. If no adjustment has been made to the CGOP in Business Indicators, then did the application of a lower inventory valuation actually increase the GOS in the National Accounts in the latest quarter? Could differences in seasonal adjustment account for all of the difference? Which indicator is then the more accurate representation of underlying business profit performance? As mentioned, non-mining industry performance is an important indicator for how the economy is really transitioning.

At best there is a question over the real direction of profit growth at an industry level. I have put this to the ABS for clarification.

The second point relates to the slow-down in growth of Compensation of Employees.

Employee compensation is the largest proportion of National Income at 50% and provides some basic context for the scope of spending growth in the economy.

The accelerating growth in employee compensation since the December 14 quarter has been consistent with an improving labour market at the same time. Except in the latest quarter, when growth in compensation more than halved between the two quarters.

Source: ABS 5206.44

I’ve compared the growth in Sept (Sep v June) and Dec (Dec v Sep) by state (5206.44) in the chart below. Breaking the data down to state level gives some indication of performance differences between mining and non-mining states. It’s not a perfect proxy.

Only in WA and ACT did the growth in compensation of employees improve over the last two quarters. In WA, the best thing you can say is that employee compensation didn’t continue to fall.

Source: ABS 5206.44

Most of the slow down between the two quarters can be attributed to the private sector which accounted for two thirds of the slow down.

Private sector employee compensation growth slowed the most in NSW – again, the engine room of the so-called transition – from +2.5% to +1.1%. This is actually consistent with my previous labour market update highlighting that NSW labour market was no longer looking as strong as it had been.

VIC had the highest quarterly rate of employee compensation growth in December of all the states. Although growth has been slowing for two quarters now, it is still around the average:-

Source: ABS

The main problem state is QLD – the decline in private sector compensation of employees has been accelerating over the last two quarters – the first time since the GFC:-

Source: ABS 5206.44

This is unfortunately at odds with the previous labour market update, which showed employment growth in QLD still at its peak as of the end of 2015.

The situation is similar in South Australia – private sector employee compensation growth has slowed over the last three quarters and has now turned negative in the December quarter.

Growth in employee compensation in WA has been negative for the last four quarters, but in the latest quarter, it has stopped declining, which means it’s still on its lows. In TAS and NT growth in employee compensation also slowed to virtually zero in the latest qtr.

Only in ACT did the growth in compensation of employees accelerate higher in the latest quarter:-

Source: ABS

Across most of the larger states, growth in employee compensation looks like it is slowing, if not outright declining. I’m using the eastern seaboard states (especially NSW and VIC) as proxies to gauge the ‘transition’ from mining states to non-mining states. The original point was about highlighting the slowdown in employee compensation growth between the two quarters. Most of this slow down can be attributed to NSW, VIC & QLD, with NSW by far the biggest contributor to the slow down between the two quarters. It could be a one off for NSW as there is no established trend there at the moment, but this outcome is consistent with my previous labour market outlook for NSW. This puts a dent in the narrative that the economy is transitioning well.

But there is more.

This slowdown in the growth of employee compensation in the December 15 quarter came at a time when growth in hrs worked has been accelerating higher over the last 3 qtrs. The growth in hours worked in the latest quarter is the second highest since the GFC and growth accelerated from 0.4% in the September quarter to +1.17% in the December quarter.

Source: ABS

This has brought the annual rate of growth close to pre-GFC highs. Growth in hours worked has been accelerating since late 2012.

Source: ABS

Yet, output hasn’t grown along with hours worked. In fact, output per hour worked (labour productivity) has been slowing since late 2012 and has started declining.

Source: ABS

In the December quarter, labour productivity declined by -0.6% to bring the annual decline to -0.4%.

The concept of “unrequited input growth” was raised in a Productivity Commission report into falling Australian productivity (source: Productivity Commission Report, “Australia’s Productivity Growth Slump: Signs of Crisis, Adjustment or both?” April 2012):-

“And so, in proximate terms, the decline in MFP [multi factor productivity] growth was associated with ‘unrequited input growth’ — strong acceleration in input demand that was not matched (or stimulated) by an acceleration in output growth. This is the key to understanding Australia’s much poorer productivity growth. Explanations must tell us why Australian businesses used a lot more inputs, without getting more growth in output ”

This was from a paper written in April 2012, so is not referencing this current labour productivity situation. The quote goes on to say that such a situation is not sustainable:

“The notion of unrequited input acceleration does raise the question of how such a phenomenon could be sustained. Typically, output growth provides the additional income needed to fund additional growth in inputs. Consequently, unrequited input growth does not make financial sense, unless there is another source of income growth. Chapter 2 also shows that profitability not only held up, but actually increased in the 2000s. The extra input accumulation was fuelled at least in part by increased profits and profit expectations. Clearly, productivity was not the source of growth in output and income that it was in the 1990s. Rather, the broad productivity trends of the 2000s seem to have been more the outcome of strong input growth driven by marked changes in prices and profits.”

In other words, the ‘returns’ were generated by increases in, and expected increases in, prices including commodity prices, rather than higher productivity generating greater profits.

We no longer enjoy those ToT benefits. Which brings me back to the idea of sustainability of input growth (increasing hours worked) without getting more output growth as a result. The annual growth in hours worked chart suggests that in recent times, when growth in hours worked has resulted in negative labour productivity, hours worked has started to fall. We are now at that stage of the cycle where labour productivity growth has turned negative and we’ll see whether this higher growth in hours can be sustained.

So far ‘rebalancing’ or transitioning has seen higher hours worked but no discernible increase in output growth, and in fact, if you use the Business Indicators data, declining company profits across mining and non-mining in the latest quarter. In the absence of price growth, this is not likely to be sustainable.

So how can Household consumption be the main driver of economic growth?

My final point on the December GDP result and the idea of the transitioning economy, relates to our single largest driver of economic growth at the moment – households.

The big news from GDP was the strength of household expenditure and its resilience in the face of our transitioning economy.

Whilst the contribution from households is large, the direction of spending growth has remained fairly steady over the last few years – not accelerating growth. The current annual rate of growth in real household consumption expenditure is now +2.9% (+4.6% in nominal terms). On a quarterly basis, growth pulled back only slightly from +0.9% in September to +0.8% in December.

Source: ABS

Compared to recent history, growth in household spending has been growing at a fairly consistent rate of just under 3% for the last 18 months.

This rate of growth is not great when you consider that the rate of household consumption growth has been much higher in previous years. But how could household spending be any higher? The context from National Income shows that employee compensation growth (and wages) has slowed considerably over the last five years and in some states, employee compensation has recently turned negative. This has translated into slowing growth in household gross disposable income as well.

Gross disposable household income growth has been slowing since it peaked in 2007 at +12% annual growth – growth is now running at +3.1%. Adjusted for CPI, gross disposable household income is only growing at 1.4% in real terms. This rate of growth is low and is slowing:-

Source: ABS

Maybe the real question is how household consumption expenditure growth has remained at this constant level while household income growth has been slowing?

One reason is due to falling net household saving. Note that the ‘net savings’ measure is actually a calculation of the difference between income and spending of households. As spending increases faster than income, net saving falls. This is what has been happening since the peak in net household saving since mid-2012. In the last year, net household saving has fallen 15%.

Source: ABS

This fall in net saving is partly funding the growth in household consumption.

The other important source funding household spending growth is household debt. While growth in household disposable income has been slowing and is now at a relatively low point, real mortgage debt as a % of real GDP has been rising to its highest point – accelerating in fact since mid-2014. The stock of outstanding housing debt now represents 85.5% of real GDP (total real private debt represents 140% of real GDP):-

Source: ABS, RBA

Compared to household disposable income, household debt now represents in excess of 175% of disposable income.

It seems we might be pinning our hopes on a transition based on continued spending by households that have been facing lower income growth and greater levels of indebtedness. Whilst the GDP top-line results look good, the underlying factors say that the success of the ‘transition’ is on shaky ground.

Source: ABS

Source: ABS